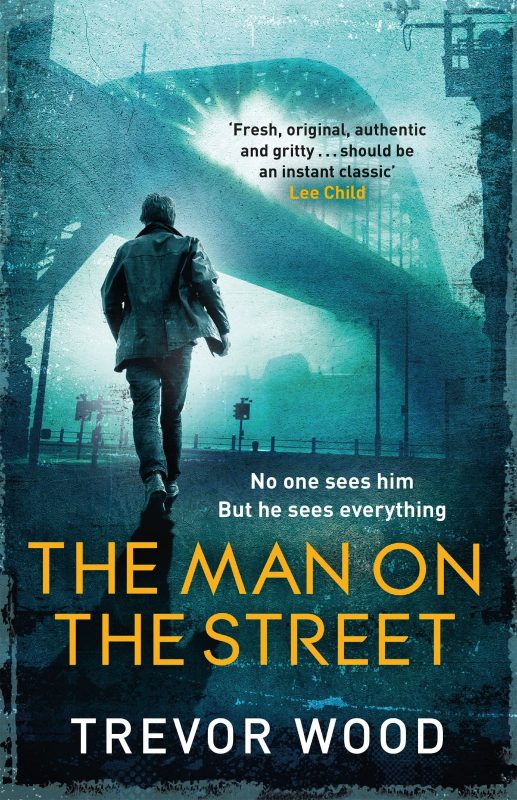

Chapter 1

Leazes Park, Newcastle, June 1, 2012

Jimmy didn’t have a watch. He liked watches well enough, but these days they were more use as currency. The last time he’d found one, in a bin behind one of the big houses in Jesmond, he’d swapped it for some dog biscuits. It didn’t matter because he could always tell what time it was – or near enough as made no difference. Like now. It was somewhere between 3 and 3.30 a.m. He used to be more precise, always within ten minutes one way or the other he reckoned, but since they brought in the late licensing laws, the mixture of noise and light from the bars and clubs had messed with his head a bit and he was sometimes out by an hour or more. It was easier here though, quieter. Leazes Park wasn’t his normal patch, but he liked to keep on the move. It was harder to hit a moving target.

His favourite spot when he first came back to Newcastle, six months ago now, was just behind Greggs in the main street. The warmth generated by the ovens seemed to stick around all night. When you were hungry though, the lingering smell of cheese pasties could drive you insane. On the plus side, you sometimes found a few in the bins, past their sell-by date but good enough for the likes of him and Dog. Then some bastard put spikes in the ground to stop people crashing there.

This wasn’t a bad spot though. The late-night revellers tended to stay clear. No one wanted to walk home through a dark park, not even the nut-jobs, so the chances of someone pissing on you in your sleep were pretty low, unlike on the street where you were invisible by day and a wanker-magnet at night.

He’d found a spot under an old beech tree behind the tennis courts where he and Dog could rest up; where no one could see him. He could see them though. There were others here, some he knew, some not. It used to be same old, same old, but new faces on the street were common now, more so during the day when the pretend beggars appeared, but even at night the numbers were growing.

He could make out a shape on the bench near the path that ran along the top of the bank, on the far side of the court, underneath the only lamp post still working. At least they hadn’t fucked with the benches. A lad from York had told him that the council there had bolted armrests on to the middle of them to stop people sleeping there.

Gadge reckoned one of the Polish lads used to crash in a tree on the edge of the park, for safety. Daft bastard broke his arm when he fell out. Good job the hospital was just across the road. Jimmy didn’t really believe that one; Gadge told a good story, but mostly that’s what they were, stories.

A crack from somewhere behind him made him jump. Jimmy sat up, hugging his sleeping bag around him and putting a restraining hand on Dog who was on his feet, growling softly. He looked around. Though the moon was hidden by thick clouds, his night vision was working well, one of the bonuses of sleeping like a … whatever the opposite of a baby was. An old man? A dead man? That couldn’t be right; dead men sleep great.

There was nothing to be seen. A false alarm. He patted Dog on the head and the mongrel terrier curled back down near his feet.

Jimmy watched as the figure on the bench stirred in his sleep and rolled over. It was Deano. The Cossack hat was a dead giveaway. Gadge called him ‘the Twat in the Hat’, but Deano didn’t seem to mind. He reckoned it was well toasty. Jimmy watched as Deano pulled his hat over his ears and rolled back, his face turned towards the bench, the hulking shadow of the football stadium behind him, towering over the four-storey town houses that flanked the park. That’s when Jimmy heard the voices. Men, at least a couple of them, laughing in the distance.

Sound travels miles in the park at night, so at first, he wasn’t sure where they were, but then he caught a glimpse of two men through the trees by the lake, heading down past the derelict pavilion, their bright green, high-vis jackets standing out in the darkness. Coppers, Jimmy thought. The bane of his life – even though he used to be one, sort of. It was like they could smell him. He pulled himself further back beneath the tree, well out of sight of the path.

‘I wouldn’t touch her with a bargepole,’ one of them said.

‘You haven’t got a bargepole, mate,’ the other said, laughing, ‘more like a Twiglet.’

‘Piss off, Duke,’ the first man said. As they came closer Jimmy could see them more clearly through the mesh fence surrounding the tennis courts. Laughing boy seemed huge, like a wardrobe on legs.

‘What have we got here?’ the small copper said, spotting Deano on the bench. They were now standing underneath the lamp; Jimmy recognised the big one. He’d got previous. Dog started to stir again, but Jimmy calmed him with another pat.

‘You can’t sleep here, pal,’ the big copper said, nudging Deano with his baton. Deano didn’t move.

‘Oi!’ he shouted, nudging him harder. ‘Get up!’

Deano rolled over slowly and looked up at the pair standing above him.

‘Come on, cloth ears, get moving or you’ll get my boot up your arse.’

Dog growled again and the smaller copper turned and peered across, towards the noise. Jimmy edged even further back into the shadows, dragging a reluctant Dog by his collar, hoping he wouldn’t start barking.

‘Can I stay here just for now?’ he heard Deano say in his child-like voice. ‘It’s nice.’

‘No you bloody can’t,’ the big copper said, hauling Deano off the bench and, in one movement, hurling him down the steep bank into some thorny bushes next to the court fence.

‘Steady on, Duke, he’s just a kid,’ the other one said.

‘Just a kid my arse; he’s as old as you.’

Deano clearly knew better than to complain. He scrambled out of the bushes, crawled up the bank and headed back to the bench.

‘Where you going?’ the big copper said.

‘Get my stuff,’ Deano said, pointing at a small rucksack tucked under the bench.

‘No you’re fucking not,’ the big copper said.

‘But I need—’

The kick caught Deano straight in the balls. As he fell, a second kick caught him on the side of the head.

‘For Christ’s sake, Duke,’ the smaller copper said, grabbing his friend’s arm. The other man shrugged him off, pulled out Deano’s rucksack and heaved it over the iron railing that edged the park. He laughed and glanced down at Deano who was quietly wiping blood away from his face.

‘Now piss off, you scrounging git.’ He aimed another casual kick at Deano, but the lad didn’t need telling twice. He leapt to his feet and legged it off towards the gate at the top of the path.

‘Have a nice day!’ the mean bastard shouted.

Jimmy watched as the two policemen headed off, to make sure they left the park. He’d learned the hard way that when you stick your head above the parapet it gets shot off. But the guilt of inaction still burned in his throat; even Dog had moved away from him.

‘Bollocks to you, Dog,’ Jimmy said. ‘Not my fight.’

Listen on Audible

Listen on Audible

audible

audible