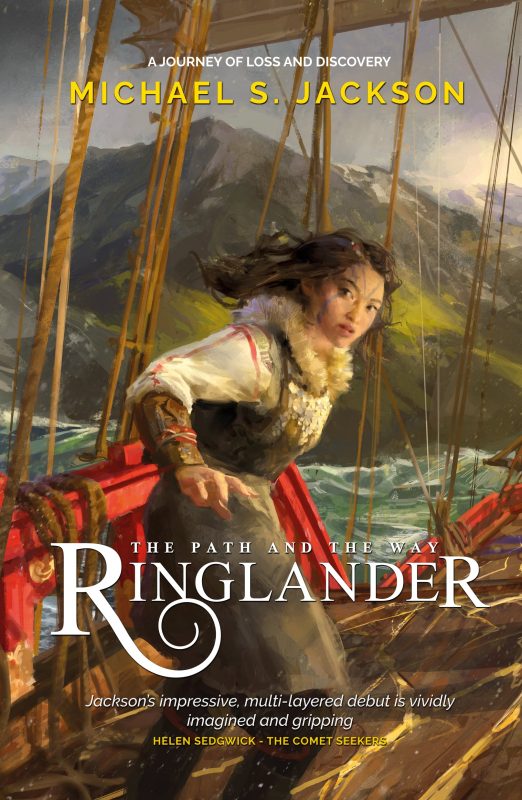

Chapter 1 - Kyira

Kyira dragged her belt blade through the slaver’s throat, acutely aware of each tendon and muscle tugging on the fine serrated edge. Warm blood burst out over her hand; she had taken the vein. A momentary flutter, but she clenched the bone handle and completed the movement, as though she were simply preparing a pig for the Feast of Moons.

Even as the slaver fell, another emerged from the mist, taller than the last by two heads and twice as wide. His minksin swirled behind him — a wide canvas larger than her sleeping mat. She set her feet as he barrelled towards her, spinning a two-handed ortaxe above his head with one arm. Kyira dove and slid into the plug of ice she had hauled out barely an hour before and sprang back to her feet.

“All he wanted to know was if you had any friends out here, girl,” rasped the huge slaver. “The Kin would save you all. Might even let you go if you had a map or two.” His deep-set eyes took her in. “I guess not. Still, that ain’t no problem of mine. My reckonings tell me that you’re out here all by yourself. There ain’t no one what can save you.”

“Get back!” snarled Kyira, swiping a nervous fish blade out in front.

“I don’t think so, girl. Not me. You might be quick enough to catch old Okvik off guard, but not me, little one. Not Siskin.”

Kyira shifted left, feigning an escape.

“Oh, no you don’t!” The slaver rushed forward, realising too late that the ice hole lay between them. His feet slipped as he tried to fight his own momentum but he slid awkwardly in, coming to a stop with one arm and leg stretching out of the hole. “Curse you!” Guttural pants punctuated each word. “Forbringrs curse you!” His muscles shook as he struggled, searching for purchase on the sharp edges.

Kyira held her belt blade low but steady. The slaver’s ortaxe sat just out his reach but it was heavy enough to rebalance him. He clearly had the same thought.

“Raaaa!” He thrust out his arm and clasped the weapon’s handle, but the move shifted his weight the wrong way and he slid into the hole like a fat seal. She turned away.

No splash? “Shiach!”

She spun on her spot and peered into the ice hole. The slaver was holding his head a barely a finger’s breadth from the slushy surface, the metal point of his ortaxe rammed into the wall, giving him enough tension to hold himself rigid against the inside. He was strong, but those great muscles were shaking, and he was holding his breath. It was silent again, but not the silence when useful things were being done. This was that special quiet that came before death, before the old ox was slaughtered, before the dog that had bitten its master was put down, before the pig…

Kyira side-stepped around the hole, away from the slaver’s head and tapped the crook of his knee with her moccasin. The tension broke, his grip failed, and the slushy Laich swallowed him with barely a sound.

She stared at the gently bobbing ice, as though his wide mottled face might somehow emerge, angry and dripping, ready to exact hateful vengeance, but she knew better. His pig heart had beat its last.

She forced her gaze up, scanning the Laich. Mist was not unusual for this time of year, nor this time of day, but it had come on so quickly she had barely finished setting her fishing line when the hills had vanished behind a thick veil. At least she knew exactly where she was, as Pathwatchers always did.

The first slaver was sprawled a few paces away, surrounded by dark spatters. She collected her oil tin but didn’t relight it. Slavers always travelled in twos, but there might be more out there yet. She rewound the wick and pressed it into the congealed mixture, then tucked it away in her waist bag.

She squatted over the slaver’s corpse, holding her belt blade over his ruined neck. There was no coming back for this pig, but it never hurt to stay cautious. His face was black with Lines but there was no elegance to them, and they had no story to tell — nothing she could make out anyway. She touched her chin, feeling the raised patterns and following them to her cheeks. Each of the five Lines marked her cycles since becoming an adult, the beginning of her story, her aspirations, and her life. A Pathwatcher’s life.

She blinked at the slaver. His Lines were those of a fishman, a chaser of sharks, and yet here he was inland, chasing down simple folk. The Sami had a name for those who ignored the Lines written into their skin: Culdè, and this man’s aspirations looked as though they had been forgotten many moons ago. Where his skin wasn’t Lined, it was cracked and red. A Southerner, not used to the cold, dry winds of Nord, and judging by the beige patches on his breeches, he’d spent weeks, maybe months, in the saddle.

She rummaged through his pockets, ignoring the fleas crawling freely between his inner and outer garments: a dirty pipe made from a wood she had never seen before; some flint; some rolled smokeleaf; a chewstick; and a small pouch. She pulled the drawstrings and let the weight inside tip out onto her palm. There was no mistaking it, even in Nord babies sucked on the varnished wooden bulb to help them sleep. So, he was a man. A father. What sort of woman would have bred with you? Certainly no Sami, nor any other Nordun woman that Kyira had met.

A colony of dark specks crowded around a spot of blood on his furry hood, and she stood, feeling nauseous. Regardless of who he was, nobody who let themselves get in such a state lasted long out here, not least those who kept their guard down for so long. He had to have had a camp close by, she thought as she dragged him to the ice hole. The body slid along the edge, tipping in headfirst, just like his friend.

The ice plug came next, and it dropped neatly back into the hole, forcing a little water to gurgle up the sides. Pocketing the slaver’s pouch, she dipped her hands in the water and scrubbed the blood from her skin, trying to picture which sort of fire would warm her up the quickest. It was a half day’s walk from here on the Laich back to where Aki, her father, had camped and she would need to find somewhere along the way to sleep. There were a number of places: the cave upon the fourth sister above the Waning Crescent; a hidden alcove in the small waterfall a league beyond on the last sister — she might get wet, but at least she would be hidden. The cave would be best, and the fourth sister was a tall enough hill to spot anyone following.

The dark residue, colourless in the evening light, pooled with the quickly freezing water creating patterns.

She had not planned on being away from home for so long, but the new season’s taimen living in the Laich were far too fat to just leave to the orca, and twilight was the best time to catch them. It was why she had spent most of the day cutting such a big hole through the ice. It was lucky it was not yet spring — things might have gone very differently if she had been fishing for eels.

A noise blew in from the north bank and her breath caught. A whicker. She stared into the darkening night, but the mist gave nothing away.

The belt blade slipped back into a sheath at her waist with a reassuring rasp, its bone handle still sticky with the slaver’s blood; the rack of four taimens went over her back, the clasp hooking through the loop on her shoulder; and lastly, her fishing line, which she spun quickly around the gnarlnut shell, was thrust into her waist bag.

It was time to go.

She spared the mist a final glance and sped off over the ice towards the far bank. The frozen estuary was narrow, but she was closer to the northern side than the south. Hard ice crunched underfoot so loud she was sure someone would hear, but she pushed on, reaching the south bank’s shoreline well within an hour. She slowed as she approached the rocky outcrops — if there were more slavers, they couldn’t have guessed she could cross the Laich so quickly. In any case they were mounted and she was not.

Weaving deftly between the rocks, she leapt over the thinnest ice and onto the shore. The ground was permafrost all year round here along the Taegr — the line that marked the upper circle of the world — and was perfect for running. Only her brother Hasaan could match her stride, but not for long, a fact she used to enjoy teasing him with. The ground was a smear of colour beneath her as her feet carried her on, bounding lightly over and up the fat waist of the second sister, upon and around the ridge of the hill’s back and onto the shoulder, the first of the two peaks.

Hopping over a decoy fork, Kyira carried on through into the rough grass until the slightest change of colour showed she had re-joined the ridge path. It was as clear to her as if it had been lain out with lines of oil and set alight. She stopped and turned back towards the Laich.

Three mounted slavers stood at the northern shore, black scratches on the pristine white of the Laich. Kyira ducked. They might not be Nordun but the horned nara they rode upon were, and they would catch her up and run her down before three hours had passed.

She took off, sprinting along the nape — it was slower but the rough ground would hide her shape. The line led her all the way to the shoulders of the third sister, a ridge that led to the highest hill on the Waning Crescent. She trudged carelessly through a large patch of snow as though she was heading down into the valley. Her pursuers would expect her to seek shelter in the vale before risking the ridges on a moonless night.

She raced along the ridge, trying to cover as much distance as she could before first dark. Panting, she dropped off the Waning Crescent and entered the second valley, a tree valley, named not for the trees, of which there were none, but for the multiple ways in and out. It was filled with glacial boulders and was a perfect place to rest and escape if she needed to.

She jumped down the few feet onto the first boulder and ran its length. Ten paces exactly. The next one, six, she thought, already in the air. She landed and rolled forward then again she was air-bound, springing over the stones with ease. The last rock was flat and although she couldn’t see it, she knew it was five paces narrow and twenty-and-one-half paces long, with a short step to the grass. She hopped onto it, then jerked as her foot bumped into something that should not have been there, sending her spinning into the sharp edge of a split boulder. The ground barely had time to greet her before she was back up, staring at the dark lump. It was a grey glacial boulder ten paces wide and fifteen long, deposited many moons ago, and had lived at the bottom of this valley since then. Yet here it was, uphill.

“What are you doing up here?” she said, feeling along its edge. “You did not walk, and neither were you pushed. You are too fat for that.” It had been split right down the middle. The ragged edge led to a face that was almost shiny, like the rock had spent a lifetime against a smith’s forge. What force could split a rock in two?

Irrational panic bubbled in her breast, her heart pounded as though the slavers had somehow appeared before her. She drew a ragged breath, willing the shapes around her back into their still, stoic forms. She was alone.

Breathe.

Her skin tingled and her vision narrowed. The vale grew darker, but somehow clearer as a new focus settled upon her.

Breathe.

Her mother used to call it magic, but it was no such thing. It was just a way of tricking her body into listening. And feeling.

Breathe.

A sympathy with the world, from the crisp air to the frost at her feet.

Breathe.

A snowcrick chirruped on her right, looking for a male to fight. Another to the left. There must be a new nest nearby. She listened as they spoke to each other, imagining that she could understand their noises.

Breathe.

A soft wind bristled at the hairs on her face bringing a new smell.

Wood smoke. There was a fire close by. The vale was almost completely black now, but there… there was something…

Someone was breathing, and it was heavy and laboured. Kyira crept around the split boulder, and pursing her lips, whistled three short bursts, warbling the sound. There was a slight pause before the corresponding call floated in on the breeze.

The dim glow of the fire appeared from between the boulders, flickering shadows coming from the low wall of snow and rocks. A fire built in haste. Kyira stayed just outside of the light.

“Hasaan?” said a man.

“It’s me, Aki.” She manoeuvred into the hollow depression, skirted the fire, and knelt at her father’s side. This was a well-chosen camp; they were well hidden here. “What happened? Why are you out here? It is not safe.”

“You think I cannot handle myself?” asked her father, throwing his climbing stick clattering against the stones.

She reached over and moved the stick’s leather wrapping away from the coals. “There are dangers. Aki, your skin is so pale.”

He drew back. “Child, I am perfectly able—”

“Aki,” said Kyira, pulling the taimen from her back and sitting them on the grass.

“Aki, Aki, Aki! Iqaluk is my name, Kyira! Aki is a name children use. You are Lined now. Act like it.” He nodded back up the hill. “Where is your brother?”

“He is not with you?”

“He goes his own way. He always has.” Even insensible, the words were meant to cut her. “He will be fine. He went climbing this morning.”

“So, you are fighting again.”

“That boy has much to learn!” snapped Iqaluk, grabbing the stick and shaking it at her. “As do you.” He smoothed down his long grey beard.

“And what have I to learn exactly?”

“How to choose your own path for one!”

“I do that which makes me happy, Aki.” Sickness rose in Kyira’s stomach. “Besides, I know a Stormwing’s call when I hear one.” It was probably the most lame rebuke she could have chosen, but it was hardly the time to get into a debate on the course of her life.

“Even a Culdè knows the Stormwing, not least during mating season.”

“A Culdè? You think I do not know myself!” Kyira spoke before she could stop herself. “Well, I knew you were here, hiding, in this… hole. What if that stone rolled back down? What would you do then by yourself.”

“Did you see it? No? I did. It is broken in two, girl! Cracked like an egg, as though there were nothing inside but… but yolk.” The last word vanished into a bout of ragged coughs.

Kyira placed a tender hand on his forehead. Fever blood. Only the beginnings, but it would get worse. “Where are you hurt?”

Iqaluk tried to bend forward then after a second patted his thick skin jacket near his kidneys. Carefully, Kyira spread the coat, smelling the blood before she saw it. Her cold hands touched searing hot skin drawing a hiss between clenched teeth. She had never known her father to show pain. He was the strongest man she knew. She lifted his coat and shirt revealing angry red skin surrounding a puncture wound. She pulled the fishing line from her bag and knotted it around the jacket at his back to keep the wound exposed. “Don’t move, Aki. I’ll be back.”

The low bushes and plants hid their medicines well this far north. Thorns and poisons kept all but the most determined animals at bay, but Kyira knew what to look for. Under the last rock and a few inches under the earth was a bulbous, woody weed: a type of inedible tuber root with soft red fur that was smooth one way but not the other. It was smaller than she would’ve liked but it would do. Heedless of the mud, she dug her hands beneath and gathered up a few wriggling grubs, before stuffing them in the pouch she’d taken from the slaver.

Back at the fire she peeled away the outer layers of the tuber, and sliced along the root’s length with her blade, careful not to touch the wet flesh. She waited until its distinctive smell permeated the air and then thrust it into a pile of snow. After a few minutes of preparation, the cold root and the grubs were infusing over the coals in her father’s kettle.

Save the sound of bubbling liquid and crackling fire, a familiar silence hung in the air. It was the same quiet that usually followed their family meal, as they sat around tending to skins or sharpening knives, a time where no one spoke, and all felt at peace as their hands worked. Before she died, her mother would wind twine from sheep sinew, expertly weaving thin strands together, plaiting it over and over until it was tight and strong. Her deft fingers always moved so quickly.

Kyira wafted the sickly-sweet kettle steam then plucked out the red root with her knife and dropped it into the coals.

“Aki?” Iqaluk didn’t move. “Aki?” He mumbled something. The fever blood was getting worse. “Iqaluk.” His eyes opened at his name. “Iqaluk,” she said, grabbing his head. “You must drink this.” He sipped slowly, spilling some of the hot liquid over himself. By the time he finished he had only regained a little colour.

“Who did this to you?” She felt a fool for asking, seeing as she already knew the answer, but she had to keep him talking.

Iqaluk lay back, breathing deeply. “Slavers,” he said, his voice high. “They were mounted.”

“What did they want? What did they take?”

“Everything, child. Everything. They raided our supplies. The animals are all dead and burned. We have nothing left, Kyira. Nothing.”

“We will rebuild. We have done it before, Aki, and we shall do it again.”

His hard stare softened. “Your words fill me with hope, but sometimes words can be as meaningless as the canvas upon which they are printed. You have to drive change and forge your path!”

Kyira nodded but couldn’t stop herself taking a long breath. He had been talking like this more and more of late, imparting wisdom as though he might die in the night.

“Not every fight needs to be fought, Aki.”

“I will not let these men get away with this! We will only find ourselves fighting more of them come spring. Let us kill this one at the seed.” He propped himself up on a wobbling elbow. “Where is Vlada?”

Kyira worked her fingers. “I don’t know. I sent him up to hunt, just before they came.”

Iqaluk sat up. “Before who came?” Drops of sweat had appeared on his brow and beside his nose — the medicine was working.

“I was attacked.”

Iqaluk’s eyes widened, and he tried to get up. “By who?”

“No, please, Aki. Please. I am fine. I dealt with it.”

“Good. Slavers care only for coin. They would sooner sneak into our camp in the dead of night and raid us in our sleep, only so they can attack the next day with the odds in their favour. That is if they didn’t slit your throat while you dreamt. They are fools and cowards.”

“They wanted maps.”

“Maps,” snorted Iqaluk, reeling like a drunkard. “Kyira, when the breathe of the Forbringrs carved the first paths, it was the ways of the Kartta, the first of our people, that shaped the world.”

He wasn’t talking sense. “Shaped the world? Aki, please.”

“Listen to me, Kyira! It is up to us to shape the world. The practice of documenting the paths was abandoned centuries ago, we must pass it down… as treasure to the next… next generation.” He winced and his eyes rolled. “Even the slavers know… would know this.”

“Aki, you must sleep.”

“Yes, you are right. I will need my energy if I am to climb Hasaan’s peak tonight.”

Kyira’s mouth opened in protest but was stilled as her father’s hand rose to her cheek following the Lines on her skin.

“My daughter. You are as fierce as your mother ever was, and more. You will make a fine Pathwatcher. If only your brother were… if only… if…” He closed his eyes, and his chest began rising and falling with the heavy rhythm of sleep.

Listen on Audible

Listen on Audible