Chapter 1

Goodmews, South Dakota

One

Early spring, 1965

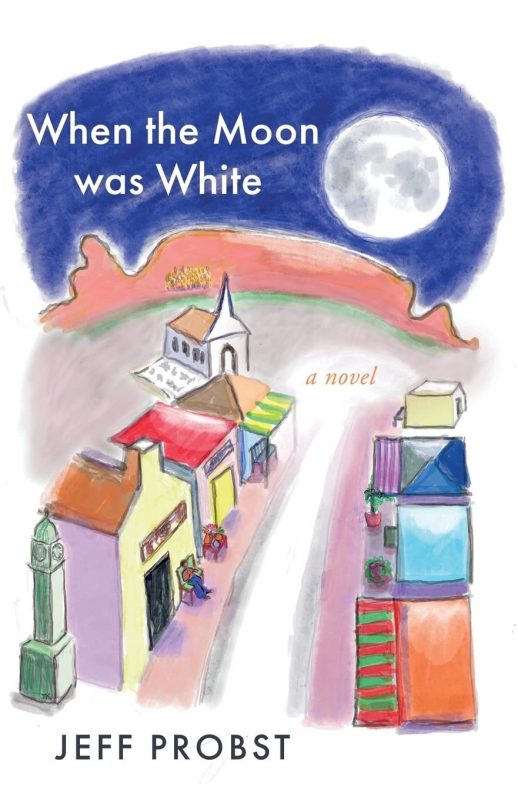

Francine had always doubted it could happen. That a person, visiting a place for the first time, could be so taken by it they would decide to stay. But on her first Goodmews evening, gazing up at the moon as she stood alone on the salmon-pink pavement, bathed in the front gardens’ white-flowered fragrance, she said to herself, Yes, the moon is the moon; Goodmews’s is no brighter than any other. But is there something in the way it hangs above the orangewoods? The way it reflects off the Mars-coloured cliffs?

And I thought my heart belonged to Arizona.

The TV programme had been about the striking brightness of the Goodmews moon, at least in the eyes of its residents, but the town too had beguiled Francine. At first she’d been disorientated by all the bendy streets, but after a few days she got used to seeing windows and chimney stacks directly ahead as she walked along the rows of houses. She’d also found the Goodmews accent disconcerting; it seemed too harsh for such a gentle-feeling place. But she heard no bitterness when she listened more carefully, and to her ear the discordant twang began to dissolve into something that seemed to her more like a dark chocolate that was coating a softness inside.

She often ended up on Goodmews Way, and twice she had stopped outside the church, obscured by scaffolding. It recalled to her the pictures she’d seen of Gaudi’s basilica in Barcelona and struck her as Goodmews’s own bandaged creature. But beneath its timeworn boards and blackened bricks, she could sense its balanced beauty.

On the last morning of her visit, Francine did her Orangewood Drive amble again. Even though at times she rued the fact that her knowledge of the outdoors got in the way of merely enjoying it, the simple act of walking almost always made her feel good. And as she carried up the gently rising lane, appreciating nature’s gradations of shades, she thought, Is there anything more wonderful than walking by yourself, looking at, thinking, what you want.

She passed a manurey-smelling field of sheep, chomping and cropping bright green pasture, enclosed in one of the low stone walls that criss-crossed the hills. She stopped to watch a lamb scratching at its face with its hind leg, seemingly in time to a bird tweeting, then looked back towards Goodmews. Would a Martian think it was home, as it ruminated on the terracotta colour of the cliffs? From up here they looked like rose madder, a washed-out red she liked experimenting with.

As she walked on, she could smell what she thought were Shasta daisies, then saw it was cows. Their mottled black and white made her think of the moon, with its bright rays and peaks, and the darker face of the Man. Then she smelled the pineyness, and soon the grove towered up – giant orange poles fronded with green. She went through the stile and walked in, weaving through trees on barely visible paths that were now floored in leaves as slippery as magnolia petals. It’s the sort of place, she felt, that you wouldn’t see litter, even a banana peel.

Off to her right the gamboge tree jumped out at her. It was much shorter and thinner than most of the orangewoods and obvious with its lemon-like fruit, but she was surprised at how assuredly she’d found it again, and circled it to confirm what she’d known the first time. It was clearly ripe enough to make extracting its colourful sap worthwhile.

She took out her bamboo cup from Happy Goblet Massage, attached it to the tree’s trunk and with her penknife made small spiral incisions in the bark, just above the cup, and watched one milky-yellow drop fall into it. It was tangible proof of what biologists studying the area had determined: orangewoods are also found elsewhere in the world, but only here did they co-exist with gamboges.

A pine needle floated down, like a small bird treading air.

She watched for the next drop. The plodding Stones song ‘I Am Waiting, I Am Waiting’ came into her head. As the Indians had apparently once said, ‘yellow pain’ is what gamboges bled.

I’ll return in five minutes to see what I have. She walked back to the path she’d come from, and continued deeper into the grove than she’d been before. A piece of paper tacked to a tree stopped her in her tracks.

THE ORANGEWOODS

TOOTHPICK BEHEMOTHS OF SILENT GRANDEUR

It looked like someone had written it with blue pen, though the words were faded; they’d no doubt run in the rain or from the grove’s greenhouse moisture. She liked what it said. It made sense. And she liked the idea of someone tacking up their take on the woods for others to happen upon.

She took out her pen and a piece of paper and copied down the words.

Back at the gamboge tree, a few beads of sap glistened up at her from the bottom of the cup. It would take time to fill up, months probably.

Maybe it was too close to paths to be hidden, but she’d leave it as it was, as a symbol of the promise she’d made to herself to return to Goodmews one day.

Listen on Audible

Listen on Audible